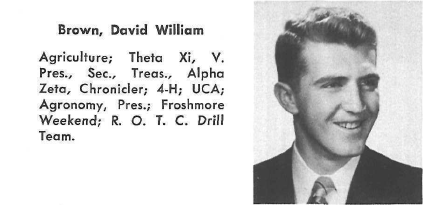

Shown above is an interview with Dave Brown (class of 1952), who was a WHUS DJ in 1949. He graduated from UConn with a degree in agricultural economics. He offers fascinating insight on radio and what it was like to be on campus during those times.

Brown wrote a piece to go along with this video. It’s collapsed below.

Dave Brown’s Text

The later 1940s-early 1950s setting

So, I would start with some of the things that were on our minds a lot in the late 1940s. Besides European WWII recovery, there was a current Korean War. We men were all “draft bait” — subject to be drafted for the military. It was very hard for a college senior to get a lasting job if you were subject to the draft. And that’s what led me to go into graduate work. I was waiting to get drafted and finally volunteered to be drafted. I had a heart murmur from scarlet fever when I was a kid, so I flunked the physical. Sort of … if there were a real emergency, I would be taken.

The other thing that was lurking was “McCarthyism” — accusations led by Senator Joseph McCarthy that many persons and groups were un-American communists. Quite a few professors were kind of afraid to say much, or express opinions. There was a lot of uneasiness. It wasn’t until 1954, when I was in M.S. studies at Cornell, that professors in universities started to speak out.

World War II veterans in our midst had important influences on us

But positive influences were in the background when I was a UConn student. They came especially from all the World War II veterans around me. Many wanted to have the kind of college experience they had missed. Some with gray hair wore freshmen beanies and went through initiations just as we younger students did!

And then, around 1951-53, you started to have professors who themselves had been World War Two veterans. They had finished grad school and were showng up as assistant professors. Robert Peters, the man who became my major professor in agronomy at UConn, was one of those — from Iowa, after he had been through war stuff, did a Master’s at North Carolina State, then a PhD at Ohio State. I became an undergrad helper with his weed-control research and preparation of his teaching materials — wonderful experience!

For example, I remember one WWII vet in an agronomy class who had been in on construction of the Alcan highway from the northwest US, through Western Canada, up into Alaska, to help avert threats of Japanese coming from that side. If you study climatology, as you head North, first you have trees, and then shruby taiga, and then barren tundra. And what they call permafrost. So he told one lessons they learned: They had a big Caterpillar bulldozer and would idle it overnight, so they wouldn’t have problems starting in the morning. So what do you happened? The warmth of the engine melted the ice and the whole rig just sunk. down into the marsh. So there were things like that from the veterans’ own experiences that we gained from.

And then there’s a whole thing about the veterans’ wives, many of them very sharp. When talking about their post-war university years, people would say the wife should get a “PHT” (Putting Husband Through) degree for enabling her spouse to earn a PhD degree, while sacrificing her own career. Often a veteran’s wife a filled a key role on campus as a lab assistant, secretary to the dean, or such. You had very talented women who may or may not have finished a college degree, and who might have a kid or two, who were important parts of the fabric that made universities like UConn tick. Only some of these wives were able to have their own advanced-education day later on.

And so, my UConn years were a blending of the old and new, and a time of a lot of changes, with many influences from World War II veterans. By the time I was a senior, many of the veterans had graduated. More of the students by 1952-53 came directly from high schools. I found these younger students pretty boring actually. after having learned so much about the real world from the veterans.

Early low-key steps toward Black integration and leadership

Another part of early 1950s UConn was low-key racial integration without making a big deal about it. The president of our 1953 class was David Holmes, Black fellow from the Hartford area. He just kind of emerged — was leader of a dorm in North Campus … not a loud, smooth talker or anything like that. And then he went on and did good things in Connecticut.

And who do you think was our Graduation Commencement speaker? Ralph Bunche — the pioneering international-minded Black who helped shape and lead the UN and related initiatives. He was the one who gave our talk. And again, we didn’t make a big show of it … was just kind of in keeping with the times.

Needed part-time and summer work at UConn to get by, but gave me great experience

I had some savings from high-school and summer jobs, and an Esso (now Exxon) 4-H scholarship that was $100 a year toward $600 or more tuition. At UConn in 1949-50, some part-time jobs were available at $1.00 per hour or so I had to figure out ways to work part-time 15-20 hours a week.

My first job was in the UConn Creamery, helping to bottle milk, make ice cream and such. Things were ok until… until I made a mistake and somehow connected up the big chocolate milk vat with the big white milk vat. There was no white milk that day! They didn’t say anything, but I was quietly relegated to the attic of the old dairy building to clean out old stuff.

Then I came to appreciate what delivery guys go through. The small UConn dairy van used to bring milk to faculty and others in homes near campus. One wintery day the regular delivery man wasn’t there, so another worker and I were asked to substitute. they know and you don’t appreciate what delivery guys one day the I had to help there used to be a Yukon the Yukon dairy used to deliver milk to all the professors around you know around backer campus South Campus and so I was asked to help a subsidy to guy do it that day. We were out there to like 11 o’clock at night trying to deliver milk to unhappy people. It goes pretty slow when you’re trying to learn a route in not very good weather.

By my sophomore year I had decided to major in agronomy, and that opened up part-time work opportunities with that section of Plant Sciences. At first it was routine things like analyzing soil samples that growers around the state had sent in. Later they had me doing things on my own, like preparing soil profiles and a dried-weed collection for use in teaching. And carefully handling experimental plots on the UConn agronomy farm down below South Campus. And running some statistical tests (with small desk calculators in those days). Besides part-time during my 2nd, 3rd and 4th years at UConn, I worked on the agronomy farm one whole summer. Great experience for my stat courses and joint agronomic-economic projects later on!

Horsebarn Hill wasn’t just for horses

Those big barns on Horsebarn Hill did indeed have prize Percheron and Morgan horses. But back in the early 1950s and before, UConn had a strong poultry section. There were rows of small chicken coops on the Hill too. These were to test and compare the chickens that hatcheries in the region were producing, and to see how variations in management affected these flocks. This was in close communication with UConn Ag and 4-H Extension programs that reached down into the counties.

Had links with UConn while still a 4-Her in Wallingford

I should back up to we as middle- and high-schoolers were in local 4-H clubs. Our 4-H doings were guided by Extension County Club Agents who in turn were backstopped by UConn Extension specialists. Besides the technical aspects of farm- and home-related projects, we learned how to keep records, and how to run good meetings, and how to cooperate with others, and how not to mind if you didn’t earn top prizes.

Some of the learning was on the UConn campus. And along with it was wholesome socialization. When high school seniors, we 4-Hers who were interested in becoming UConn students were enabled to be on campus for a long weekend to go to some classes and see what it was like. (That’s when I first attended an ag econ lecture!) We stayed in a dorm with a former 4-Her. And we saw how students without much money found ways to get along, like making use of food left-overs after waiting on tables for special events. The Registrar gave us a special briefing, with good perspective about UConn’s strengths and limitations.

So when I began as a UConn freshman Fall 1949, we 4-Hers already had some acquaintance with campus. We knew some of the specialists. They were heroes in our eyes, and to be actually rubbing elbows with them was nice.

Lots of new construction taking place on campus then

Another part of 1949-50 is that quite a few of the buildings which you now know were being constructed then — the North Campus dorms and fraternities … the beginnings of South Campus dorms for women … what is now the main Ag campus … a new gym and swimming pool. Older buildings were being revamped. The Student Union wasn’t there yet.

That first semester many of us men were in WWII barracks down in South Campus — wooden and drafty. On a winter’s day, snow would come up through the floorboards.

The campus co-op bookstore in South Campus also — in an old wooden schoolhouse.

The first automatic clothes washers were being put in place. Before those, many of us students actually mailed our dirty clothes home for our mom’s to wash!

We did a lot of walking to and from the main campus too. No regular campus bus service. Often slushy pathways instead of nice sidewalks.

But there was kind of a special spirit in all that too. As new buildings were completed and equipped with modern furnishings in 1950 and after, we were awed and tried to make good use of them.

Thinking back to the 1930s and 40s, what roles did radio play in family lives? Was it a golden age for radio?

Yes, I think radio came into that in the 1930s.

My early years were mostly in Connecticut. My dad was a farm manager who had grown up in Newport RI in a modest family. He was the first in the family to go to college — URI, then called Rhode Island State College. In the mid-1920s he became manager of the dairy farm attached to the Masonic Home for old people, in Wallingford CT. In 1939 that farm was cut apart by construction of a new highway. So for a couple of years And then later, we were back in RI — in North Kingstown, where my dad helped to establish a new farm (where Westmoreland subdivision now is). And then, after late 1941, we were back in Wallingford CT, on apple orchards.

For families like ours in the 1930s and 40s, a large, nicely crafted wooden radio would be a living-room centerpiece — during the Depression, a major investment. Record players started to be added to radio sets. In the 1940s, we might have also a small plastic radio in our kitchen or bedroom, and also out in the barn where my dad and his helpers worked. Radios were becoming popular additions to cars.

AM radio was the mainstay. A not too costly radio often had shortwave bands too. But it was not until the 1950s that most of us had FM, along with high-fidelity receivers and then stereo. Actually many of those big old wooden mono radios, even table models, had nice deep sounds, if well placed in a room. I had a good one with mono speakers pointing sideways to the left and right (instead of out the front). The sounds bounced off the walls and furniture, and reached our ears almost like stereo.

With shortwave in those days, you could reach around the world — if not directly, via relays. Also, there were some 50,000-watt “clear-channel” AM stations that could boom across wide stretches of the U.S. Besides some of those, we in central Connecticut could tune into a bunch of AM stations from New York and New England.

For us kids, a Monday-Friday joy was to listen to 15- or 30-minute radio series after coming home from school from about 4:30 until about 8 pm – Jack Armstrong, Captain Midnight, Tom Mix, Hop Harrigan, Little Orphan Annie, The Lone Ranger, and more. They often had breakfast-food sponsors. If you sent in a box top or coupon, you could receive a hike-o-meter, or secret-code club badge, and such. Some comic books were based on these characters.

For adults, there were the early-evening “soap opera” series, then the 6 pm news and commentators, then comedians along with serious documentaries, music and dramas.

Radio kept us really in touch with World War II events

The 1939-40 World War events in Europe became “close” to us because many of our schoolmates, teachers and neighbors had relatives in Italy, Poland, Hungary, etc. In Allenton RI, a Norwegian man delivered the daily milk to our school. One day he was crying. The Nazis had invaded his home country. That had us listening by radio more closely to those events.

When I was in 5th grade, we moved back to Wallingford CT, a few weeks before Pearl Harbor, Dec 7, 1941. Radio reporters were on the scene with live accounts relayed to the U.S. mainland. Likewise for later Pacific, North African and European war events. Good observers like Edward R Murrow and Walter Cronkite got their start that way. Reliable radio networks and news bureaus became mainstays.

World War II got me interested in shortwave listening. I had a small shortwave receiver up in my bedroom and would browse for hours for direct broadcasts, or at least live relays. Soon after Pearl Harbor, the Japanese invaded the Philippines. The few American soldiers there retreated to Bataan and Corridor forts near Manila. One shortwave report that I heard was just when the Japanese were advancing down into the caves where the Americans were holed up.

Wallingford was a factory town of about 15,000 people next to a river, with farms in the surrounding hills. It had traditional “main street” homes and stores. Elite Choate School was there too. One high school and several grade schools that we either walked or took a bus to. Old New England families … more recent arrivals from Italy, Poland, Hungary, Ireland, and elsewhere.

We had a pretty full spectrum of World War II impacts – local young men drafted … silverware and other kinds of factories shifting to war needs … rationing of gasoline, tires, coffee … pushes for more food production via farms and “Victory Gardens” … pushes also for recycling old metal stuff, paper, cloth … being just 15 miles from Long Island Sound, volunteers watching at night for possible German bombers, and the upper half of car headlights taped to minimize sky-glare that those bombers could use to navigate toward factory and port towns, and likewise our window shades drawn at night.

We grade-school kids became part of those War efforts too. During our lunch times, pairs of us walked around our school neighborhood with stretcher-like wooden carriers. We went house to house to collect bundles of newspapers and sacks of squashed tin cans, and toted them back to the school basement, for recycling pickups. We wore used clothing from rummage sales. We took part in War Support pep rallies at local factories.

We farm-area kids collected the seedpods of wild Milkweeds along roadsides. Their fluffy fibers were used in life preservers, as substitutes for kapok, which came from the tropics and was no longer available.

Those of us who were 4-H Club members — with guidance from local farmers and UConn ag specialists — had vegetable, poultry, and dairy projects that produced substantial amounts of food. We learned also how to reduce post-harvest waste and to preserve for wintertime use. Among the families with 4-H kids and their neighbors, there was quite a bit of swapping of one kind of food produce for another.

With so many men drafted, farmers had problems finding enough labor, even with programs that brought some workers from other places such as Jamaica, or made use of prisoners from nearby jails. On orchards like the one my dad managed, women and school teachers from town helped out. More use was made of us kids — even pre-teenagers – after school, and during summers. By the age of 13, I knew how to prune trees … thin, pick and sort apples … drive and service tractors and small trucks. Not to mention my having milked cows, driven oxen, harvested hay, etc. for a dairy farmer up the road. And raising a Brown Swiss heifer that I won as a prize in a Conn. Dairymen’s essay contest.

We in Connecticut had quite few glimpses of preparations for D Day (Allied invasion of German-occupied France on June 6, 1944). Lots of freighters and war ships headed close our coastline up toward Canada and across to England. They were guarded by planes based near us. New 1940s helicopters were produced near Bridgeport, and their test and patrol flights were near us. Wallingford was under the flight paths of fighter planes and bombers flying to England. Sometimes, if they had a local boy on board, they would buzz the town, flying lower than I was on Cook Hill on the outskirts toward Cheshire. We kids had card games that taught us the silhouettes of planes, enemy as well as our own.

Bad news didn’t stem just from the War. I was helping our neighbor with milking chores the afternoon of July 6, 1944 when our barn radio blared out sad news about the Hartford circus fire. Some people at UConn, including an ag econ prof of mine, lost family members in that.

But come 1945, there was good news – the end of the War in Europe, and May 5th VE Day celebrations in New York and elsewhere that radio joyously reported. And perhaps more somberly because of the atomic bombings over Japan, V-J Day events in August and September.

A nice outgrowth of our World War II era

The owners of the orchard that my dad managed 1943-52 were a Jewish family who had recently come to Wallingford from northern Italy. We lived in a house on the orchard, had close friendly relationships, and learned much from them about how Fascism had evolved in the 1920s-30s, and also about the beautiful aspects of Italian cultures.

Our family relationship with them has flourished over the decades. They invited my wife and me to many of their life milestones, such as bat mitzvahs. One of their offspring, Rick Vitale, in fact became a statistics prof at UConn. He is now retired back in their original home in Wallingford. I’m still in touch with him.

How radio has helped farm people

Up-to-date weather reports and forecasts via radio have very valuable to farmers for guiding when to plant, harvest hay, spray, guard against bad storms and frost, and much more. The main radio stations had direct links with the U.S. Weather Bureau. In the 1940s, these reports came out of Brainard Field near Hartford.

For us on the hillside orchards overlooking Wallingford, avoiding frost damage to young peaches was one concern; if an unseasonal frost was expected, we would have to set out smudge pots (used crankcase oil set alight in old gallon paint cans) to create some warmth near the peach trees. The cranberry bogs near Cape Cod had similar sensitivities. In more recent years, instead of smoky pots, low-flying helicopters have been used to stir up frosty air over the bogs.

Especially in the 1940s for New England, some major radio stations did a lot to help us on farms to learn more about new methods and useful meetings. For us in Central Connecticut, our mainstay was Frank Atwood at WTIC in Hartford. He conveyed tips from UConn ag specialists, the Soil Conservation Service, and others. He told about on-farm twilight meetings where we could learn from experts in person. For the farm women he had information from UConn about canning farm produce and such. For us youngsters, 4-H related updates. And for all of us, Grange Hall potluck suppers and local country fairs that we could go to, as well as the big ones like Eastern States Expo in West Springfield.

Frank Atwood via radio had a big influence during my high school years on my aspiring to have a public-service career related to agriculture. I was thinking especially of becoming a county agent or a soil conservation specialist. You can imagine my thrill to learn, when I was a UConn student a few years later, that Frank actually lived in Storrs, near the edge of campus. One semester he sent out word that he needed someone to help around his home grounds. I got that part-time job, so had the chance to get to know him in person. Unlike the image we have of many radio personalities, Frank was very low-key, mild-mannered, and modest.

How UConn helped launch my career

Cornell University in upstate New York was considered by many as having the strongest ag college in the Northeast. I applied, was accepted and given a modest scholarship. But having to its high out-of-state tuition would have put me into debt. UConn was very strong also, but cheaper, so I decided instead to go to Storrs. It turned out to be a great experience and launch pad. As mentioned earlier, even with a couple of scholarships, I still had to work part-time and summers to stay out of debt. Often, I would hitch-hike home to Wallingford and back, and tighten my belt in other ways.

My UConn advisors said one could become a soil conservationist from any of several starting points – ag engineering, plant sciences, and more. I decided to major in the section of Plant Sciences that dealt especially with field crops and soils – agronomy. I had good experience via the agronomy focus and related courses in other fields, except for a couple of chemistry courses that most students had trouble with. Agronomy majors were well focused but required some breadth in other sciences, economics, sociology, English, etc. too.

The UConn Agronomy Section had only about 8 profs, a few M.S. students, and maybe a dozen majors in each class. So, we undergrads, especially those of us working part-time, felt that we were an integral part of the group in ways that went beyond the classroom. For example, with the women students having to be in their dorms early on weekday evenings, sometimes a faculty member would pay me to babysit while he and his wife went out. In fact, the whole College of Agriculture was like that, with the Dean sponsoring informal “smokers” (with free cigars offered!) that enabled us students and faculty to get to know one another beyond departmental lines, and to get a bigger picture of the College’s emerging roles. I kept in touch with my major prof, Bob Peters, throughout my career, and even after my retirement back here in New England.

Besides agronomy, I found myself over the four years at UConn fascinated by courses in agricultural economics. A first-semester course, Economic and Social Trends in Agriculture, gave me a wonderful beginning overview. It was taught by Harold Halcrow who, reflecting his Great Plains origins, specialized in crop insurance and related ways to reduce farming risks. He taught the course not with a “canned” approach, but by discussing recent articles by leading ag economists about current policies. I had contacts with him for nearly four decades.

A UConn ag econometrician, then-young George Judge, added rigor … gave me an A even though I got only 65 in the final exam. He went on to become a well-known author at the U of Illinois, then at the U of California- Berkeley. He too I kept in touch with … visited him in Berkeley … he sent me new writings of his as recently as five years ago.

Richard King, then a UConn ag econ grad student, went on to become a well-known prof at Carolina State U. Turned out that we were to have further links via TVA-programs in the South and USAID programs in Peru.

One semester, the UConn Ag Econ Department had a seminar series that focused on “What is Progress?” Each week featured a speaker from a different department – e.g., physics, zoology, sociology, philosophy. We undergrads who had been in ag econ courses were invited to take active part. It broadened our outlook, that’s for sure.

Came my senior UConn year, my agronomy profs invited me to go for a “distinction” degree, even though I wasn’t an all-A student … had just a 3.2 GPA, with a few C’s and even one D. This entailed two semesters of special readings, then a comprehensive written exam, then a grad-student type oral exam, with little ol’ me facing the entire agronomy faculty and the austere Botany chairman. I didn’t learn the results until nearly graduation day. At the ceremony, instead of a diploma, I received a note saying they were still printing it to say “with distinction in agronomy and with honors”.

I guess the main point I’m trying to make in this part of the interview is that, even in a large university like UConn, a reasonably alert, not necessarily brilliant, student can find personalized learning opportunities, and career starting points, and enduring relationships.

The next three years, 1953-56, found me in grad studies at Cornell and Iowa State

June 1953, right after graduating from UConn, I headed for Cornell (by hitchhiking) for M.S. studies emphasizing farm management economics. My assistantship had me the rest of that summer being part of a team who interviewed farmers about their insurance needs in a cross-section of New York counties all the way from St Lawrence in the North to Suffolk on Long Island. So, when classes began that September, I already had a good understanding of New York farmers’ situations.

Fall 1953 they had me helping a Cornell marketing extension specialist do situation-outlook newsletters, for eggs and poultry especially. Spring semester found me helping him re-gear a large ag prices class, which had been taught by a famous old prof since the 1920s. Little did I know what precedence I undid by causing the old course notes be dropped in favor of a new ag prices textbook that they had used at UConn!

By September 1954 I had completed my M.S. courses and thesis (under Bud Stanton, an up-and-coming ag econ leader), and was headed (again by hitchhiking) for Ames, Iowa to begin Ph.D. work at Iowa State under Earl Heady, who had become one of the foremost persons to study under in ag production economics. The next two years were a mix of learning high-powered ag econ, econ theory and statistics, plus valuable assistantship experience of designing and leading Iowa farmer surveys, teaching general economics, and doing joint work with tech ag, rural sociology and extension specialists.

Not to mention meeting my future wife, Jeannie, at Iowa State. She was a Master’s student in criminology and juvenile delinquency, in the Sociology Department, which was packed into the same little old building as Economics. Our casual early 1956 lunches at the Student Union blossomed by August into our being engaged. By then, I was completing my dissertation draft, and had accepted to become an assistant prof at the U of Tennessee in Knoxville starting Fall 1956. Jeannie and I were making plans to be married where her parents lived, near Washington DC, that December.

Even with heavy assistantship loads (from which I learned a lot), I managed to finish my Ph.D. more quickly than many. I wasn’t unusually smart. It was more a matter of keeping well focused, and not being psyched out by all those hurdles of passing math and language exams, and written and oral prelims for a major subject and two minors, and such.

I should mention that in Iowa and other large states, radio was an important way of reaching and informing farmers and their families. WOI on the Iowa State U campus had a large building, tall antenna, and sizeable staff. One way for students to mesh with this was to major/minor in technical journalism. They ended up with a solid blend of applied sciences and locally attuned communication skills. I wish we had more that these days rather than so many instant “experts” in the media.

Another radio enhancement of my 1954-56 Iowa experience was fuller appreciation of classical music and ethnic traditions. In those wee hours of the night, while studying, I often found myself tuning into WBBM’s low-key “Music ‘til Dawn”, out of Chicago. American Airlines was the sponsor. For years afterwards, I favored flying on their planes. Also, when surveying farmers out in Iowa counties, I could hear local stations picking up on Czech, Scandinavian, Dutch, and other heritages in their vicinity, often via church and town-square doings.

Radio in East Tennessee, 1956-58

Our wedding trip brought Jeannie and me down through Shenandoah Valley country, then up the western North Carolina and Upper East Tennessee highlands toward Knoxville. We were accompanied by radio music and talking that changed a lot as the miles passed. First were the city modes of Washington DC and northern Virginia. Then Appalachian style drawls, which themselves changed as we from one set of ridges and valleys to another. Along with several forms of country music and preaching. Mostly rural-white oriented … humble modes of hoping for better lives than those uplands and coal mining towns offered … sadness for train wrecks … appreciation for moms, beautiful natural surroundings … and more.

We didn’t get around to buying a TV for six months, so relied on radio especially then for local/national/world news, Knoxville doings, various kinds of music – Roy Acuff … Hank Williams … the Monroe Brothers … Flatt and Scruggs … Nat King Cole … Patsy Cline … Carter Family … Chuck Wagon Gang … the beginnings of rockabilly via Elvis Presley.

We absorbed a lot about Cumberland Mountain, Tennessee River, Smoky Mountain, and nearby Black histories and cultures that way. Our drives to area events (e.g., Smoky Mountain Hiking Club doings; Cherokee Valley on the NC side of the Smokies; Civil War sites in southern and central Tennessee) were accompanied by localized music on the car radio to match. Being mountainous country, we’d often have to switch stations.

The mid-50s were a time when attention to the plights and civil rights of Black persons gained momentum. A major episode unfolded near Knoxville, in Clinton TN, August 1956, when 12 Black students tried to enroll in a previously all-white school. Previous steps had been taken to prepare the way for them. But still, the students were confronted by locals. This was stirred up to serious violence by outsiders from the Ku Klux Klan and other segregationists. The National Guard was called in by the Tennessee Governor. This led to a key 1957 Federal District Court trial that attracted major radio and TV network reporters. Most highlighted courtroom dramatics. A few really tried to understand the East Tennessee setting, and how the new Federal civil rights laws were rocking the boat.

My own work with the U of Tennessee during 1956-58 had unusual turns also. Our ag econ and rural soc department head came from an Extension career. He encouraged me to do a lot of in-service training, on- and off-campus, rather than just teaching or writing journal articles. I developed new winter short- courses in farm management and research methods that were practical for county agents, credit agency staff, soil conservationists and TVA farmer resettlement workers. We used to say “people who work together ought to train together”. It was the first time that some of these different agency people had been in same room together. I taught this farm economics in tandem with an agronomy professor who went further into good small-watersheds soils management. And we then went out to do field practice in parts of Tennessee where they were working, rather than just in the classroom.

There used to be an East Tennessee interdenominational church ministers association. They were interested in rural community policy issues and options. Helping them to assemble relevant background facts and to organize their thinking turned out to be another interesting off-campus role for me.

How to boil down technical information, economics, statistics, etc. has always interested me. And how to develop visuals to go with that. (In those days, just overhead viewgraphs, flannel boards, etc.).

I have blended sociology with it also. My first master’s student in Tennessee did a study of problems with organizing soil-conservation efforts in a small watershed. How to have a unified approach for reducing siltation and flooding? You had to get the farmers all lined up from the top of the watershed to the bottom. You don’t do it just by stopping at the edge of the farm boundary. So my student and I drew on help from a professor of social psychology at the University of Tennessee. He helped us devise an attitude scale that enabled us to learn much about who were key influentials in that watershed by asking just a few survey questions. We found that a farmer’s attitude toward conservation practices depended on whom the farmer listened to most – e.g., the county agent or the vo-ag teacher – and that it was important to bring these watershed influentials “on board” right at the start.

These kinds of involvements led me to feel that Tennessee was (and still is) a much better university than many people realize.

On to other places abroad and in the U.S., 1958-93

To my surprise, I was promoted quite rapidly to associate professor with tenure in mid-1957, after just nine months with the University of Tennessee. (That usually takes 3 to 6 years.) I was age 25.

But still I got restless. International assistance overseas via USAID, UN agencies, foundations and others were expanding. Some related to broad socio-economic reforms and development. Others focused on alleviating famines via higher-yielding crops (the “Green Revolution”).

So, in September 1958, I did what some would see as a foolish thing – chucked my U of Tennessee tenure and became a visiting prof of economics with the University of Malaya in Singapore for two years, under auspices of the Council on Economic and Cultural Affairs, a small Rockefeller-related foundation. And that led to a mix of overseas and U.S. program-development appointments – 1961-63 with Texas A&M … 1963-67 with the Iowa State program in Peru, then in Ames a while … 1968-82 again with the U of Tennessee … 1982-87 in Rome, Italy as UN/FAO’s situation and outlook service chief … 1988-90 with a USAID food-crops diversification project in Indonesia … 1991-93 with Illinois’ ag university strengthening project in NW Pakistan … and a string of short-term assignments in other countries. Jeannie and I settled here in Rhode Island in 1993, but I took on several more overseas tasks.

Special examples of key roles of radio during my career

In nearly all of my overseas and U.S. postings, we made conscious use of radio in educational ways. Experienced network radio correspondents and farm-radio program directors – and questions they asked — often helped us to focus on productive pathways. In some situations, radio was a key part of personal security. Let me list a few examples:

Singapore 1958-60 There was a regional correspondent from London who covered emerging events in the Far East and whose outlets included radio. He had more perspective than many country leaders or agency heads did, like foreseeing upcoming throes in Vietnam. When socializing with him, we used to press him for added insights.

Texas A&M 1961-63 The first year, I spearheaded the launch of a new farm management extension program. Then I became assistant to the dean of agriculture. One of my roles was helping leading farm radio reporters in the state to connect with relevant Texas A&M research faculty. One thing I learned was that they did not want canned PR releases. They wanted to get technical info directly from the researchers, and to boil things down themselves.

Puno, Peru, high in the southern Andes Mountains 1963-65 I was there as Iowa-USAID economist for pilot agrarian reform projects. Among other Americans there, a sizeable group of Maryknoll priests were seeking to nudge the Catholic Church into more helpful roles out into the villages. Radio was a major “tool” that they used. The Maryknolls had a radio station in Puno that beamed out for miles across the Altiplano. They used radio to help campesinos learn Spanish (Peru’s national language), and to make them villagers aware of new rights to vote, and to become aware of new programs that would be helpful. Maryknoll radio encouraged appreciation for Inca-era cultures, music and beliefs, and blended those with Christian values and changes helpful to family wellbeing.

Iowa Dimensions of Welfare outreach program 1967-68 After two years in Puno, then two years in Lima as chief of the Iowa-USAID team in Peru, Jeannie and I lived in Ames for 18 months. One of my Iowa State U roles was being part of a special research-extension team that examined approaches for reducing poverty and other human wellbeing problems. After reviewing existing programs and institutions within Iowa, we had a series of workshops with key leaders in each “functional economic area” of the state to help shape better approaches in tune with the times. Statewide radio programs helped set the stage for these workshops. More localized radio gave more specifics about upcoming workshops and how to take part. Then statewide networking reported what was the apparent consensus for improving things, and how Iowa State U was ready to work with state legislators and others toward making those changes.

Back with the U of Tennessee 1968-82 My main role this time was, as “International Professor”, backstopping our university technical-assistance programs in India and elsewhere. Besides teaching a strong contingent of international students and former Peace Corps Volunteers on campus, in Washington DC, Hawaii, Taiwan, Ghana and elsewhere, I helped evolve special short-courses for middle-level managers and policy-level officials. Those in DC, after two or three classroom weeks there, often had a week in an outlying area of Tennessee for practical applications. We ourselves learned from that too, as rural folks often will “open up” more with visitors from overseas than they would otherwise. A couple involving radio I recall especially:

One week like that was in East Tenn, in the foothills of the Smokies, near where Dolly Parton came from. The local county agent showed how he used radio to reach people in the valleys and highland areas – not heavy-handed education, but folksy radio information blended with music and other features that people liked. And timed to when farmers were doing milking chores and such. When a local publisher found that one of our participants was a budding journalist from Central Asia, he arranged for that young man to spend the entire week learning how to run an informative newspaper on a shoestring and to mesh with other media.

Another such week was in a rural county, an hour’s zig-zag drive Northeast from Nashville. The local radio-station owner said he’d like to meet our international group. So, we drove out to the station. Which turned out to be in an old mobile home, next to a tall antenna, in the middle of a cow pasture. The radio-station owner got acquainted by asking about where they came from, how things were in their home countries, and so forth. One of our participants, from a poor Latin American country, told how bad the dictatorship conditions there were. It turned out that the station owner had interrupted his regular programming and had been broadcasting this warm-up chat live. We had a worried Latin American participant on our hands for the rest of the week! But an up-side of that week was their being in Nashville and seeing firsthand where the famous Grand Ol’ Opry was produced.

In Rome with FAO, 1982-87 As chief of FAO’s Situation and Outlook Service, lots of contact with media people from all over during those years. The journalists from the Nordic countries were especially impressive by how they teamed together toward gathering a full picture of world food and agriculture prospects and problems. One serious problem in that decade (and still) — drought in/near Ethiopia and The Sudan, made worse by meandering locust infestations and also civil wars upheavals. People were packing their things into carts and migrating across semi-desert to where they thought things might be better. But information was sketchy. In some places drought was seasonal-regular; if they could find a way to store water a while, they might be better off staying put. It’s in these kinds of situations that radio combined with reliable information can have life-saving roles.

In Indonesia with a USAID food-diversification project, 1988-90 This project had radio as a major component. The aim was to spur and enable farmers in various parts of Indonesia to shift from rice and some other traditional plantings to crops that were better sources of protein and other nutrients, and easier to prepare in urban kitchens. We tried innovative approaches for gauging situations and reaching farmers in six contrasting provinces. The usual farm-related radio came in stiff manner via a dull government station … in mid-day, when farmers were out in the fields. Our Indonesian counterparts and we had good success with interesting messages on radio stations that farmers really listened to, early mornings, before they went to work.

In Northwest Pakistan with the Illinois ag university development team, 1991-94 I worked with a Pakistani agri-rural research group who did rapid-reconnaissance surveys of villages, farmers and households to gauge kinds of changes that would be helpful and workable. Several women specialists were in that research group; they were skillful in gaining confidence of, and cooperation from, women in male-dominated settings. Radios blared most everywhere, but little of it was very informational until our progressive Pakistani counterparts got their foot in the door.

In the city of Peshawar, where I based, there was a special region-wide radio component. BBC had a studio where they shaped and recorded interesting soap-opera type programs aimed at the Pashtu-speaking people of Afghanistan and Pakistan. The BBC writers wove useful messages into these scripts, like “make sure you don’t drink water that has been polluted upstream” or “you can reduce harvest waste by doing this” or “don’t get hung up on the opium that those poppies which you grow contain”. BBC welcomed useful suggestions from my ag university counterparts. The radio recordings were sent to London. The actual broadcasts were beamed from there by shortwave.

Thinking back again to my early Connecticut and UConn years…

You’ve asked me to tell you more about early exposures to radio and interest in becoming involved.

A big early radio influence was that I realized that the 1930s Depression was not just a local problem, and that many other places were worse-off than we were in Wallingford, especially where they had unusual river floodings or high plains dust storms at the same time.

My latent disk-jockey urges were nourished summer 1949 (just before I became a UConn freshman) by a New Haven radio station that said, if you send in 10(?) Cott Ginger Ale bottle caps, you can be a disk jockey for 30 minutes and compete with others for a prize. I did that — played some disks by Art Mooney, Ted Weems, Guy Lombardo, Sammy Kaye, Weavers, and others … “Heart Aches”, “I’m Looking over a Four-Leaf Clover” … and added my own connective patter. I won a semi-finalist prize and was back again for a second half-hour. At summer’s end, they invited me back for a third, finalist show. But UConn’s fall semester was beginning and I had to skip that.

I think that New Haven experience led me to poke my nose into the WHUS studio soon after becoming a UConn freshman. It was then in the basement of the Church Community Building, I think — or in the old music building next to it. And the guys who happened to be there said something like, “Sit here a while and try cuing records, fading the pads (big sound knobs), and doing a break announcement.” And then they encouraged me to return. Which I did on several Friday evenings, as a way of letting down after a busy week.

I was really in on just the edges of WHUS. Came to know and like those who handled, or popped in, Friday nights for “Suitcase Serenade”. We were probably in a more relaxed mode than weekday or sports-times WHUS … not really part of the main programming and management. But I did hear about and was impressed by WHUS leaders like Royal Colle … followed his career in Ithaca NY with interest, though we never really met.

Back in our dorm or fraternity house, I don’t recall that we early-1950s UConn men students listened to WHUS a lot of the time. There were quite a few AM stations within range of Storrs, including some of those we had listened to in our home towns as high schoolers.

One of my roommates had a good short-wave set that picked up popular American hits that we liked … from Belgium Congo yet! After you did this interview with me, Jonathan, I did a little on-line research … found there was an international network of college radio stations, including one in Belgian Congo. It was still a colony of Belgium, so that music may have reflected tastes of expats and others in Africa who links with Europe.

But in 1949-50, information via WHUS may have meant more for women students. On week days, they had to be back in their dorms by early evening. They had fewer opportunities than men to find out what was doing in other campus circuits beyond their own. Also, the women were more into sports like archery and volleyball that didn’t get much attention from non-campus news sources.

Radio involvements as a way to rub elbows with interesting, capable people from diverse backgrounds

More broadly, there was real value for a first-year UConn student like me to have loosely structured links with an outlet like WHUS’ “Suitcase Serenade” those Friday evenings. It was a way to meet capable persons from diverse backgrounds beyond our dormmates and classrooms, and to see how they organized and improved things on their own. They sought to bring some company and enjoyment to those relatively few students who stayed on campus over the weekends when there wasn’t a ball game or something else special to stay for.

During retirement here in Rhode Island, I’ve again found something like that via amateur radio and the active Newport County Radio Club. In 2013 I qualified for a basic license. FCC happened to give me a neat Call Sign – KC1AAA. My aim has been mainly to reinforce emergency communications, key neighborhood links, and storm-monitoring needs near Newport. By taking part in the Club’s meetings, on-air connects, special field days and some social events, I’ve gotten to know very bright, interesting, well intended men and women – teachers … engineers … builders … skilled sailors … ex-airline pilots … community leaders … those using radio to spur STEM learning by young people. Some like to tweak radio transmissions to reach far-away places. Others, as I, have been thinking more of nearby needs. One niche I found for myself before I stopped driving two years ago was to create some photo-stories about Radio Club doings.

A useful radio by-product – how to buffer sounds in offices, public places, etc.

As a high-schooler, I liked to visit radio stations – small local ones as well as New York’s Radio City. How they dampened echoes, handled sound effects, etc. interested me a lot. This has been true all my life, for some reason. Like in 1997, when I was doing a volunteer assignment in southern Hungary, and they interviewed me in a small radio station, and I saw how they had found a cheap way to dampen echoes – pasteboard dividers from egg crates up around the walls.

One doesn’t have to be an engineer or architect to learn and apply key sound-buffering concepts. When I was a U of Tennessee prof, a zoologist colleague became concerned about young people were losing hearing from loud rock-and-roll music. He looked into ways to dampen room noise. And this led to his becoming an informal advisor on campus toward reducing office noises. E.g., in our department where two or more persons were sharing spaces, he suggested putting some sound-softeners near typewriters and other noise sources, and soft wall panels mounted on two-by-fours to trap sounds.

Inexpensive steps like that would have helped when I was in Peshawar in the early 1990s. USAID had enabled Pakistani ag university people to build several new concrete buildings. They had provisions for new electronics, but were like echo chambers. No internet then, but colleagues and I bought some books on acoustics, and we found a few ways to dampen those sounds that were bouncing around. Better yet would have been to design the buildings with doorways staggered instead of being opposite one another, and features like that.

Nowadays, via a few minutes’ internet browsing, anyone can learn a lot about sound reverberations, echoes, buffering and such, and how to adapt to her or his particular situations.

Which leads me to this closing thought…

The video that you made a few weeks ago in my apartment rambles on to some other things. But let me close this written version here, Jonathan.

I’m thinking that as you, Henry, and other WHUS leaders and team members prepare to move on, there are special insights beyond any classroom subject which you’ve gained. These can be a valuable, unique part of your “portfolio” and what you can offer to this world in years to come. The skills about management of sounds, highlighted above, are just one example. As you look into jobs, grad studies or whatever, I hope you’ll highlight those and choose outlets that appreciate such, rather than just trying to fit into cookie-cutter molds that are currently in fashion.

It has been a pleasure and inspiration to interact with you both, and to renew contact with UConn in this fulfilling way!

Dave Brown February 5, 2024 Middletown, RI phone 401-848-9427 email djbrown2d@yahoo.com

Table of Contents

ToggleHistory

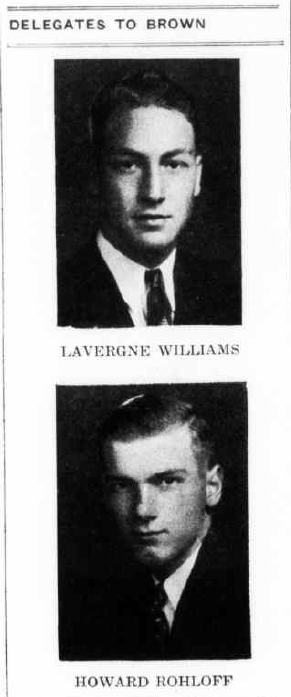

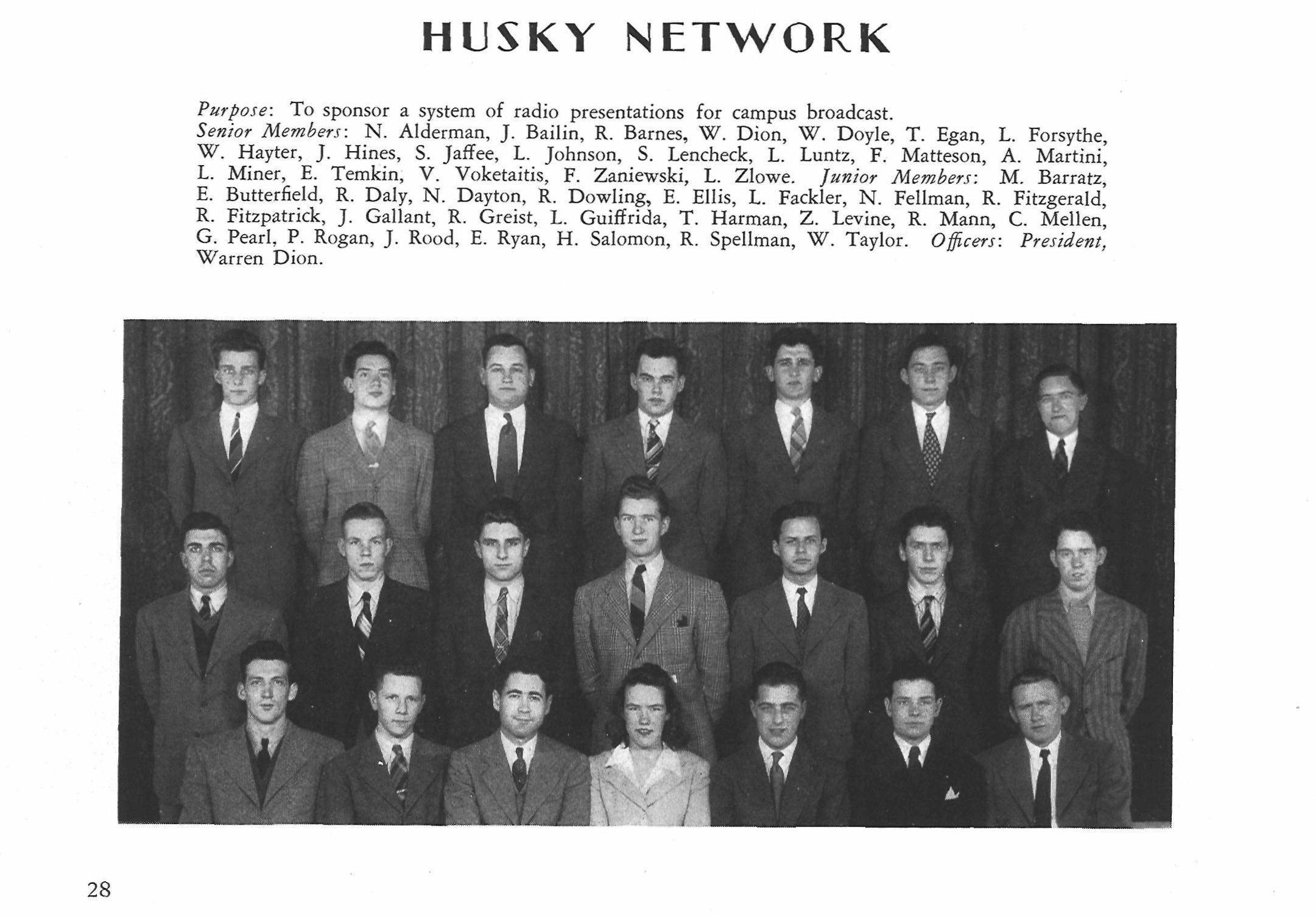

From the late 1930s to 1940, there were almost no echoes of a student radio station on campus. One big development during this time was the founding of the Intercollegiate Broadcasting System, or IBS. Established in 1940, IBS was formed with the intent of supporting college radio and the first conference was at Brown University. We were one of the first charter stations.

We sent a group of people to the IBS’s first convention in Providence, Rhode Island – LaVergne Williams, Howard Rohloff, and William Glynn.

The founders of IBS created the first AM carrier current network at Brown University in Rhode Island. The Husky Network throughout the 1940s operated as a carrier current station, often referred to as wired wireless, which refers to sending AM radio signals through existing electrical wiring within a limited area, such as a college campus. One of the main benefits was that the frequency was so weak that the FCC didn’t need carrier current stations to get a license to operate. But gone are the days of fan mail from New Zealand and the West Coast.

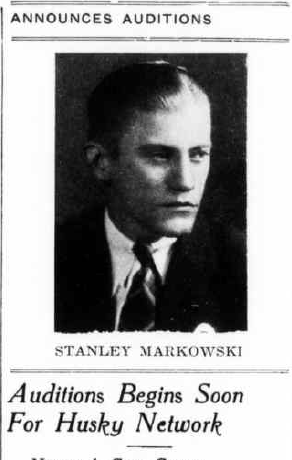

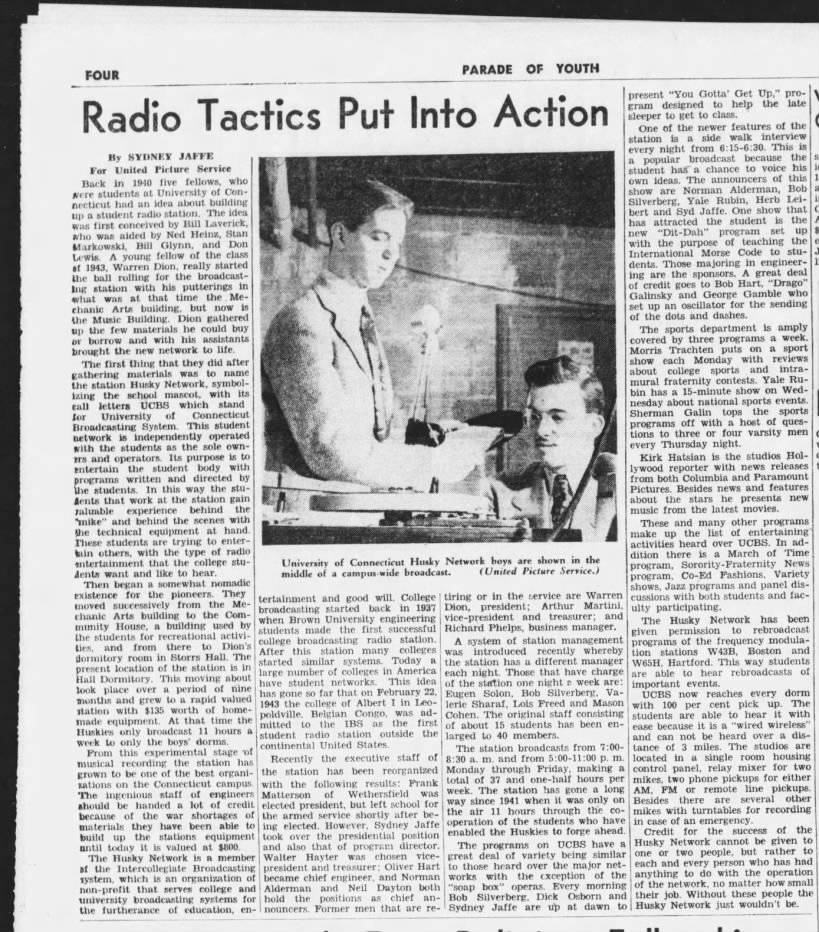

According to the Hartford Courant, there were six students responsible for getting the actual station back up and broadcasting: “Bill Laverick, Ned Heinz, Stan Markowski, Bill Glynn, Don Lewis,” and Warren Dion (’43). Dion was the one who bought and borrowed up materials and brought people together to build said station.

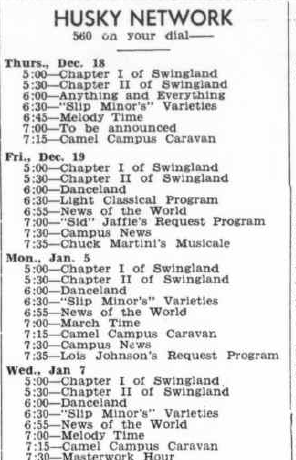

The Husky Network’s first broadcast was April 8, 1940, on 560 kHz. They held auditions at a later point but struggled to find a big enough audience. The station was commercial since part of its revenue came from advertisements.

The Husky Network also rebranded themselves as the “University of Connecticut Broadcasting Network” or UCBS. The Network continued to expand from 1942 to 1943. Army rationing for World War II combined with the draft lessened the pool of student staff and equipment for UCBS to use and it shut down in 1942. Programs included morning presentation for students who slept in, “You Gotta Get Up,” “Dit-Dah,” which taught International Morse Code, and live team-based quiz battles.

Thank you to John Babina for showing me the article below.

After three years and a World War, Daniel Harris, along with Marvin Stockberg, and a team of student engineers break the broadcast silence on May 20, 1946, on the dial between 550 and 560 kHz. They’re camped out in Koons Hall.

The station started broadcasting five days a week, Monday through Friday, from 4 p.m. to 10 p.m. time. A substantial portion of the broadcasts were to be music such as classical and jazz and F.M. rebroadcasts from WTIC.

1948 is the year that our news system receives a big upgrade. We receive a United Press teletypewriter machine. A teletype machine functions as a connector and distributor of physical information between a source and a receiver. In this case, WHUS, the receiver, would well… receive a continuous stream of printed news updates from the United Press, which was a major news agency that collected and distributed stories worldwide. The machine would churn out the latest news on long scrolls of paper. Reporters broadcast these news items to listeners. This technology made it possible for WHUS to operate professionally, providing a vital link between global events and the station’s listeners.

1947: The origin of the name “WHUS”

Where does the name WHUS come from? According to the CT Campus, the FCC in the mid-1940s required stations associated with IBS to register with them, regardless of their/our carrier current operations. No call letters in America start with the letter U, so station manager Marvin Stocking hosted a contest to select new call letters. The winner would receive an album of records. And on February 11, 1947, student Grace Cotton won an album of records, and we officially adopted “WHUS” as our moniker, with “HUS” being derived from “husky.”

WHUS Marathons

The 1950s heralded a yearly WHUS tradition that continued for more than 60 years. In 1948, students put together the charity fundraiser Community Chest Carnival, which later became the Campus Community Carnival (CCC). Suffice to say, this became an extraordinary affair, marked with parades, pie throwing games, and other festivities.

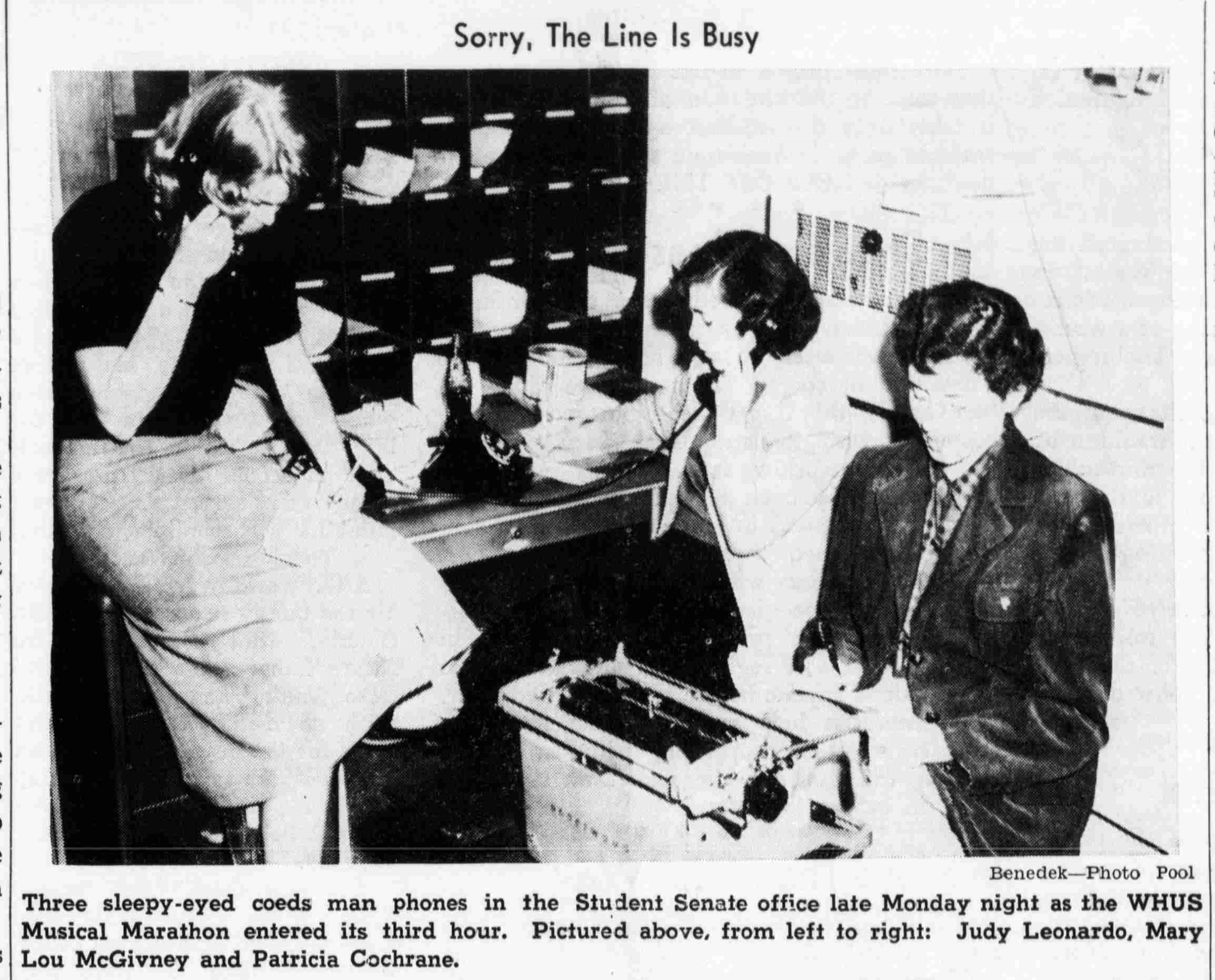

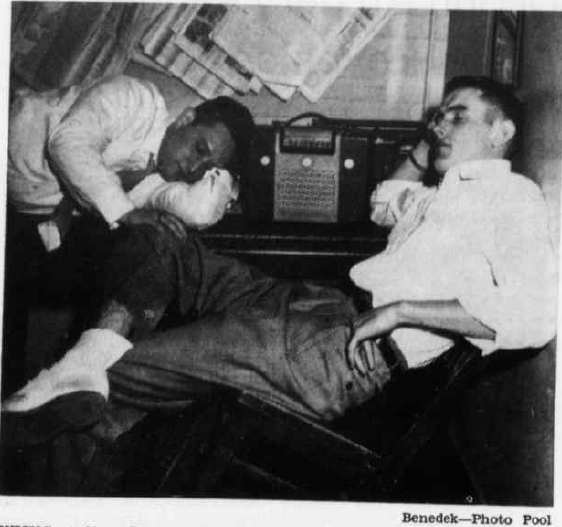

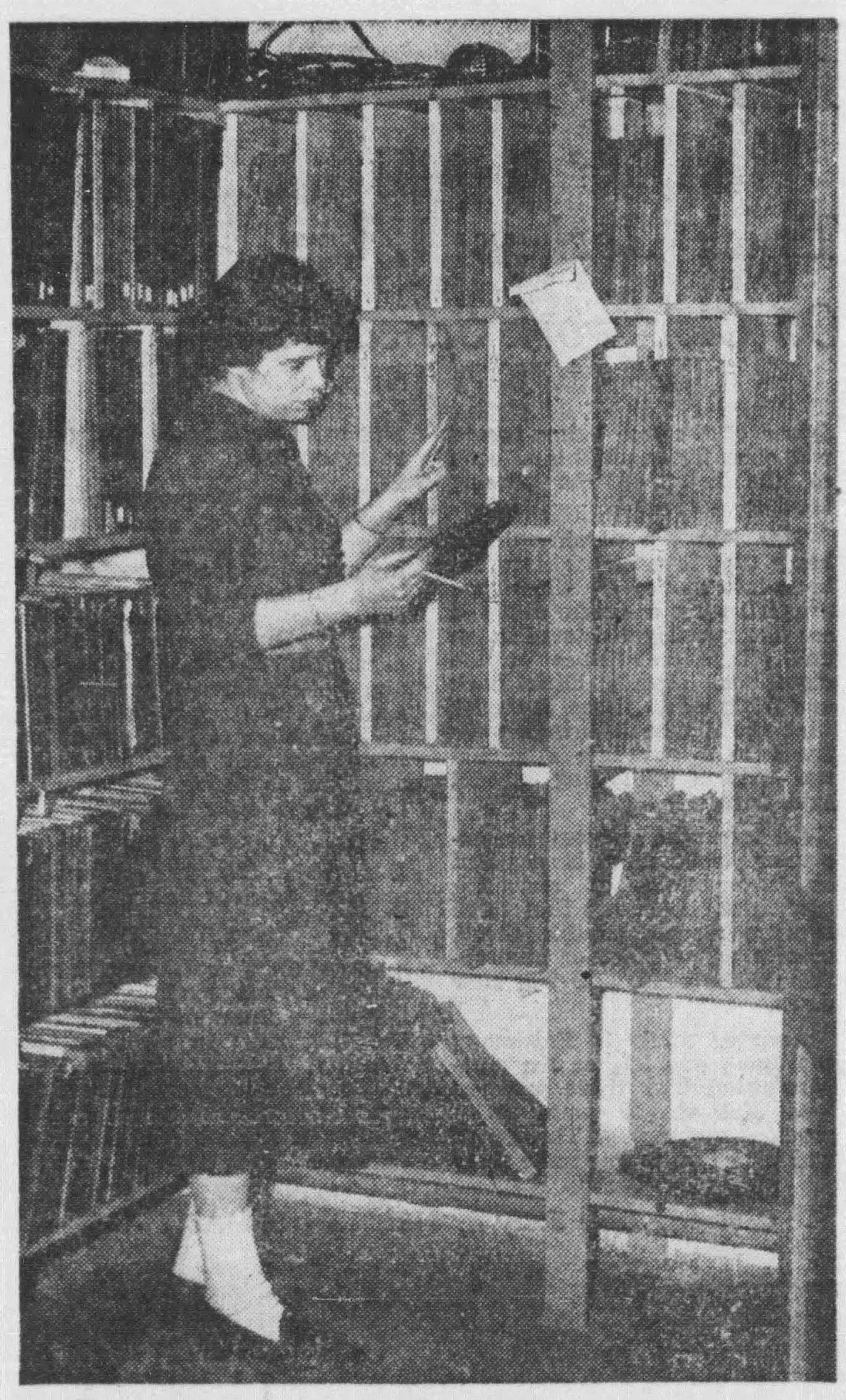

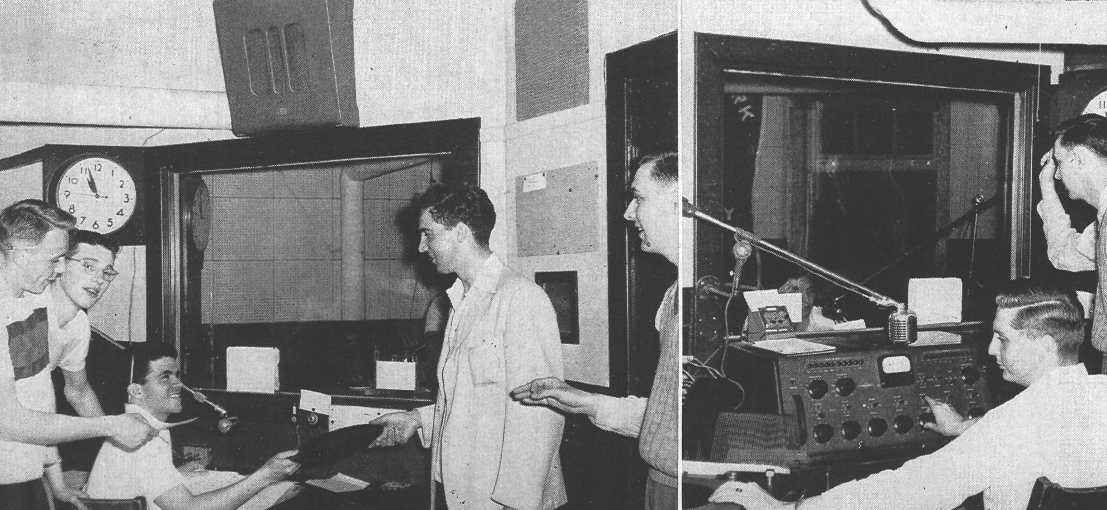

1952 was the first time WHUS participated. The station was to broadcast continuously, taking calls and pledges thru song requests, until they stopped coming in. It was a resounding success, bringing in more than $250 (almost $3000 in 2024 dollars) and going for 34 hours continuously. DJs worked 10 hours at a time and students of all calibers, including Senators and singers, came in to take calls and be interviewed.

The “Musical Marathon” continued until 1979, which was the CCC’s last year. But by no means were our marathons confined to the Carnival and eventually transformed into a station staple called Radiothon. More on that later.

The 1950s were a big time for change for WHUS. Every year, programming expanded, and students weren’t afraid to experiment. For example, there was the ear-measuring contest in 1952.

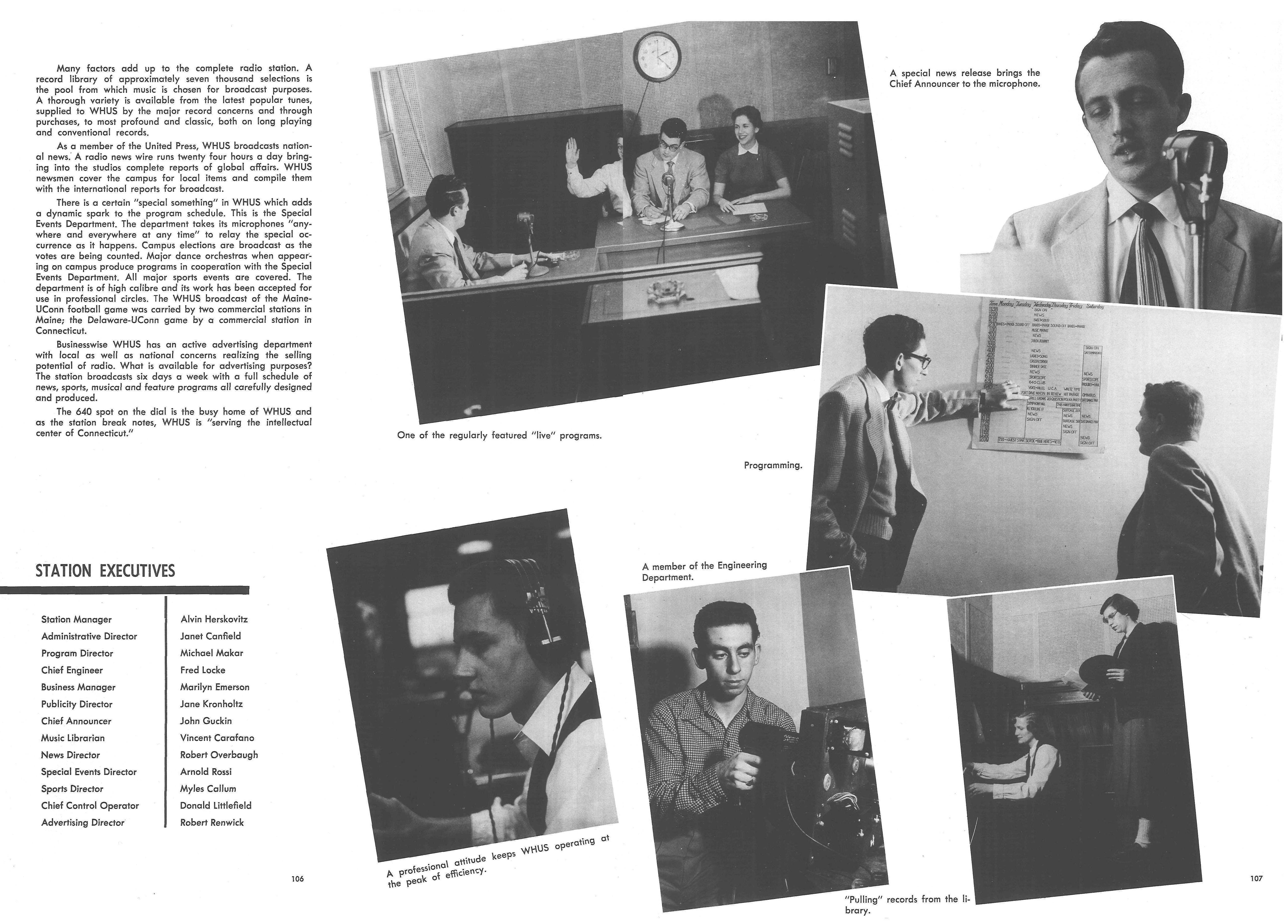

These are both from a 1952 Hartford Courant feature courant of WHUS. We emphasized variety in our programming, and a typical day could include an R.O.T.C. program, speeches by top University officials, quiz shows, and sports coverage.is the keynote of the station’s programming. We also broadcasted live music from people who came to campus like Vaughn Monroe and Elliot Lawrence.

“Another “first” for the station this year has been the contracting by WHUS with three Storrs’ merchants to broadcast all of Connecticut’s home and away basketball games on a commercial basis.” – the Courant

And in 1952, we move from Koons Hall into our shiny new studios in the newly built Student Union.

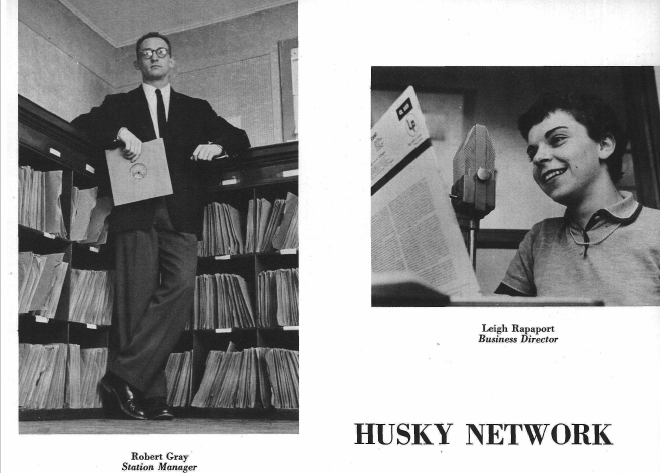

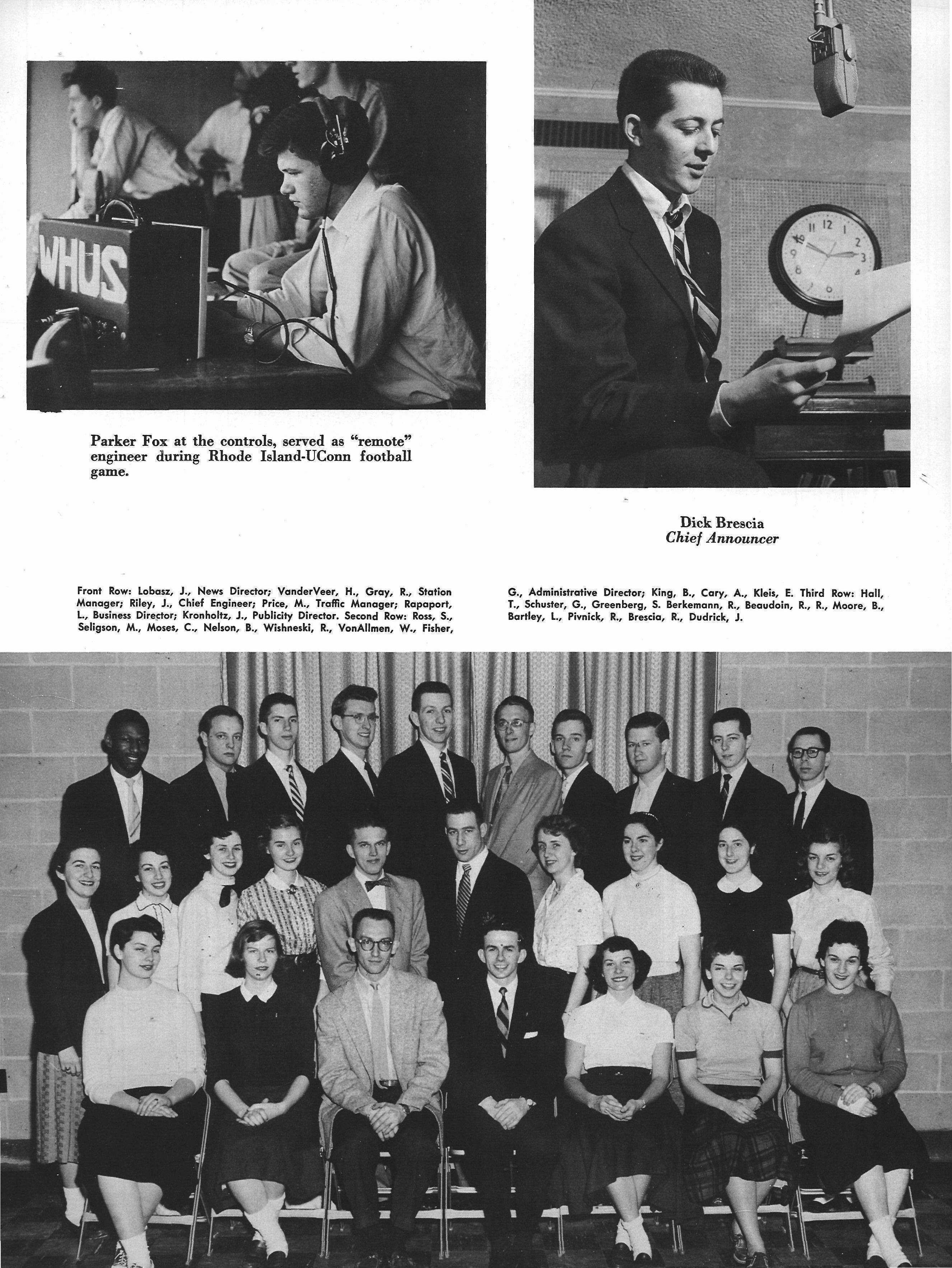

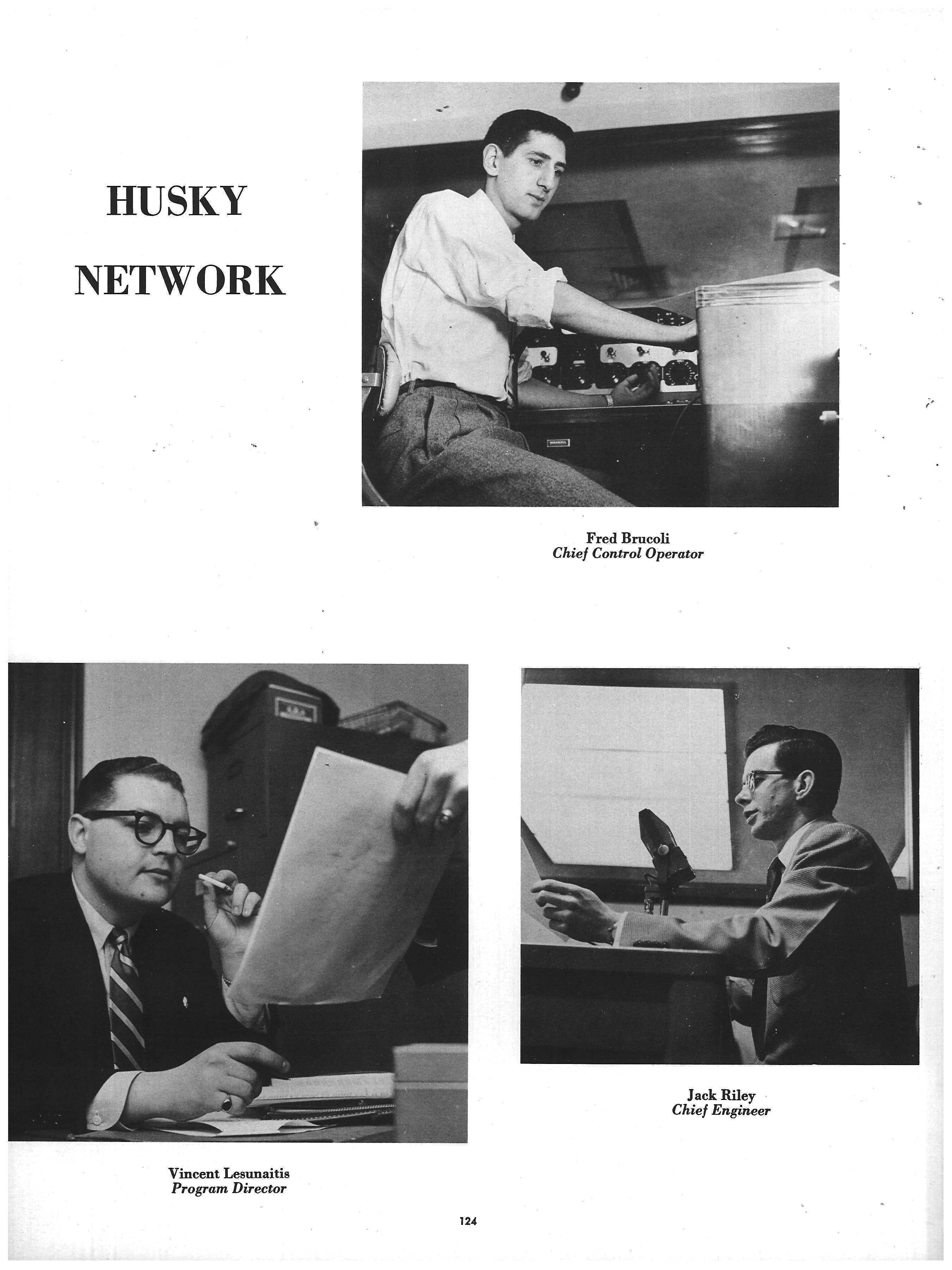

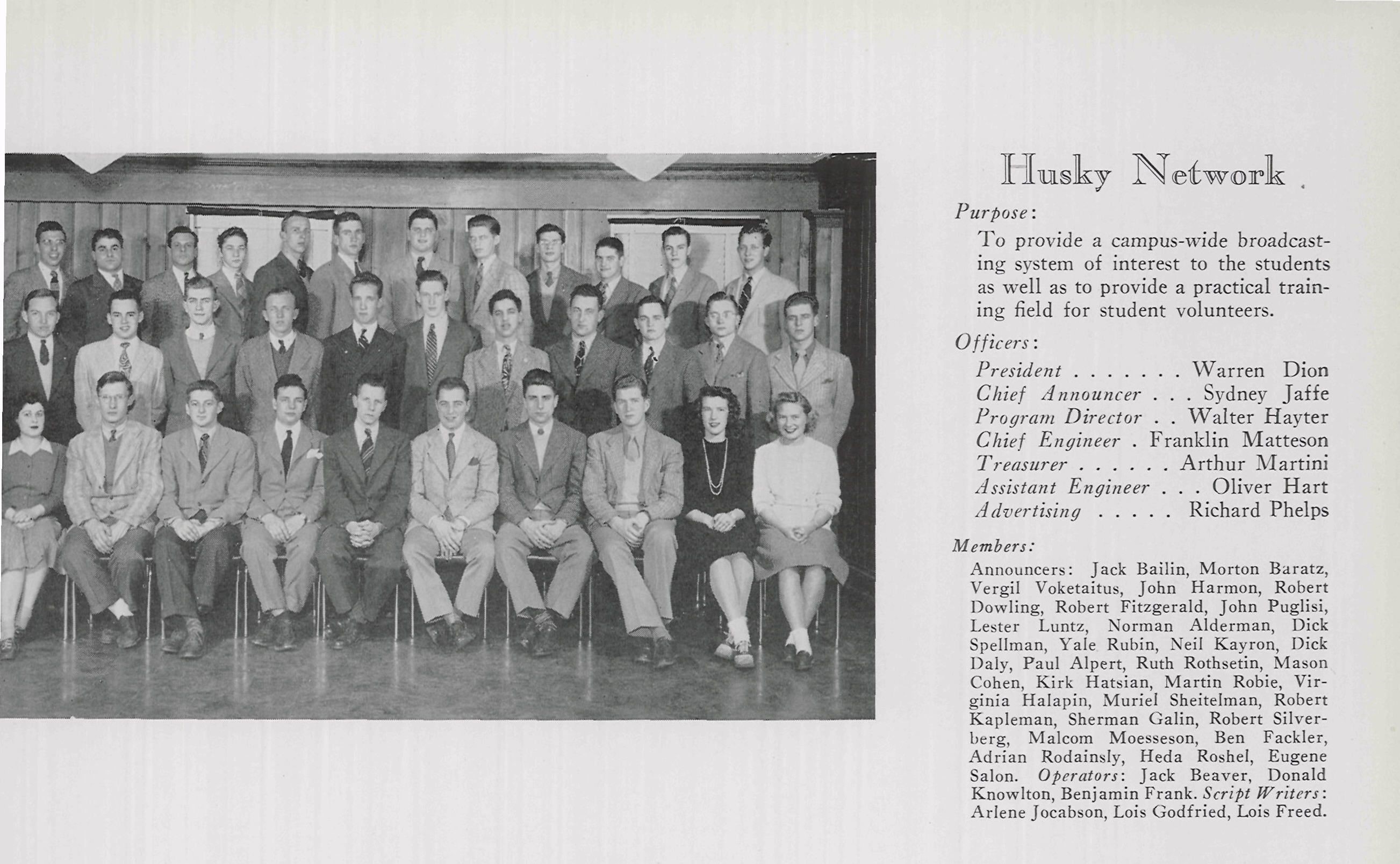

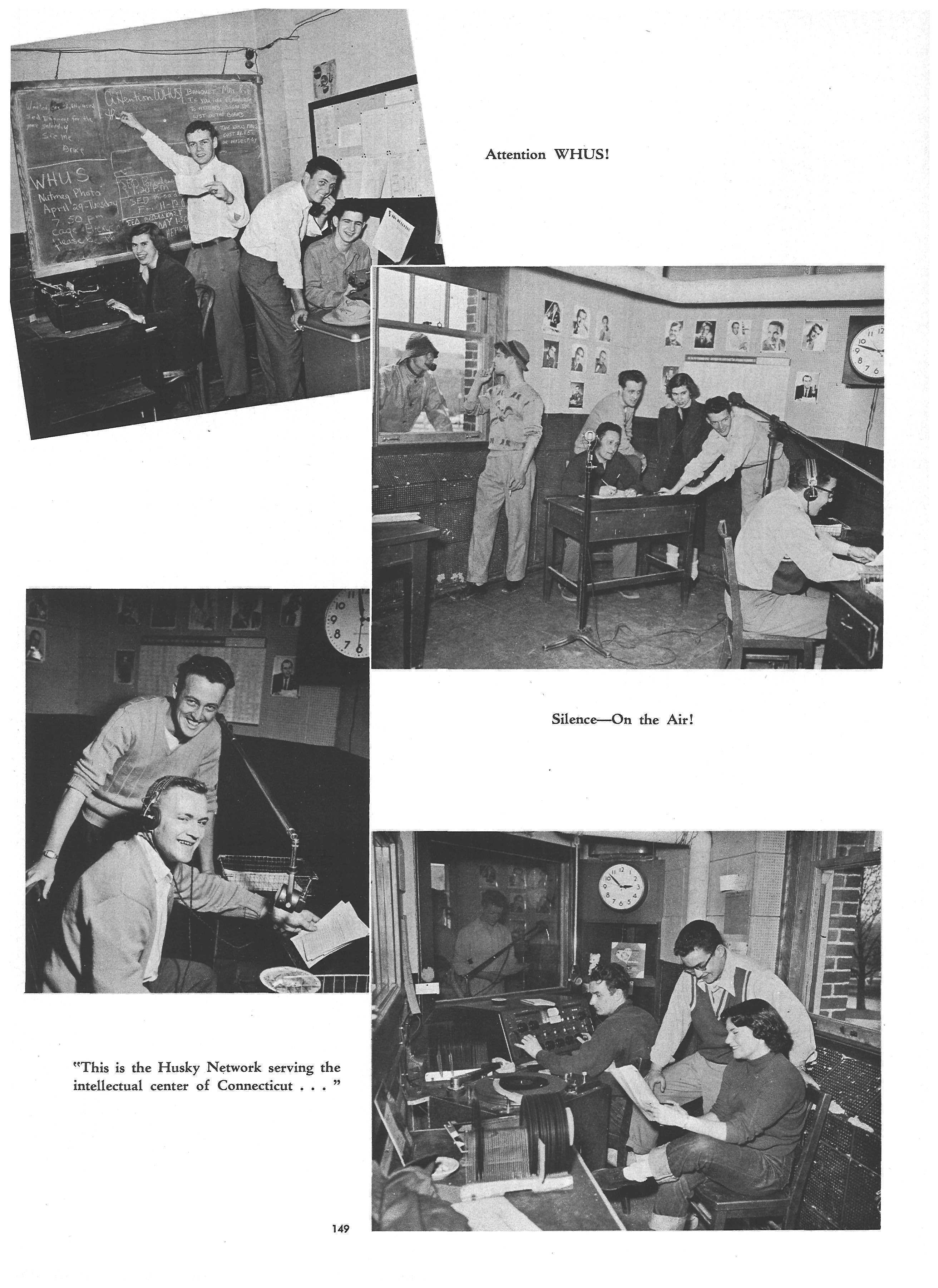

1953 Nutmeg Yearbook